The “green“ economy and its costs

Increasing consciousness of the advancing climate crisis and its worldwide effects is giving rise to a political and economic transformation, involving a move away from fossil fuels to so-called “green” energies. This process is also known as the energy transition. The current technological solutions for the energy transition require a particularly large amount of minerals and metals. New mining projects are thus being developed in order to extract so-called transition materials which are required for the energy transition, such as lithium, cobalt, copper and aluminium. Lithium, for example, is required to produce batteries for electric vehicles: in 2022, 74% of the lithium consumed worldwide was used to produce lithium ion batteries.

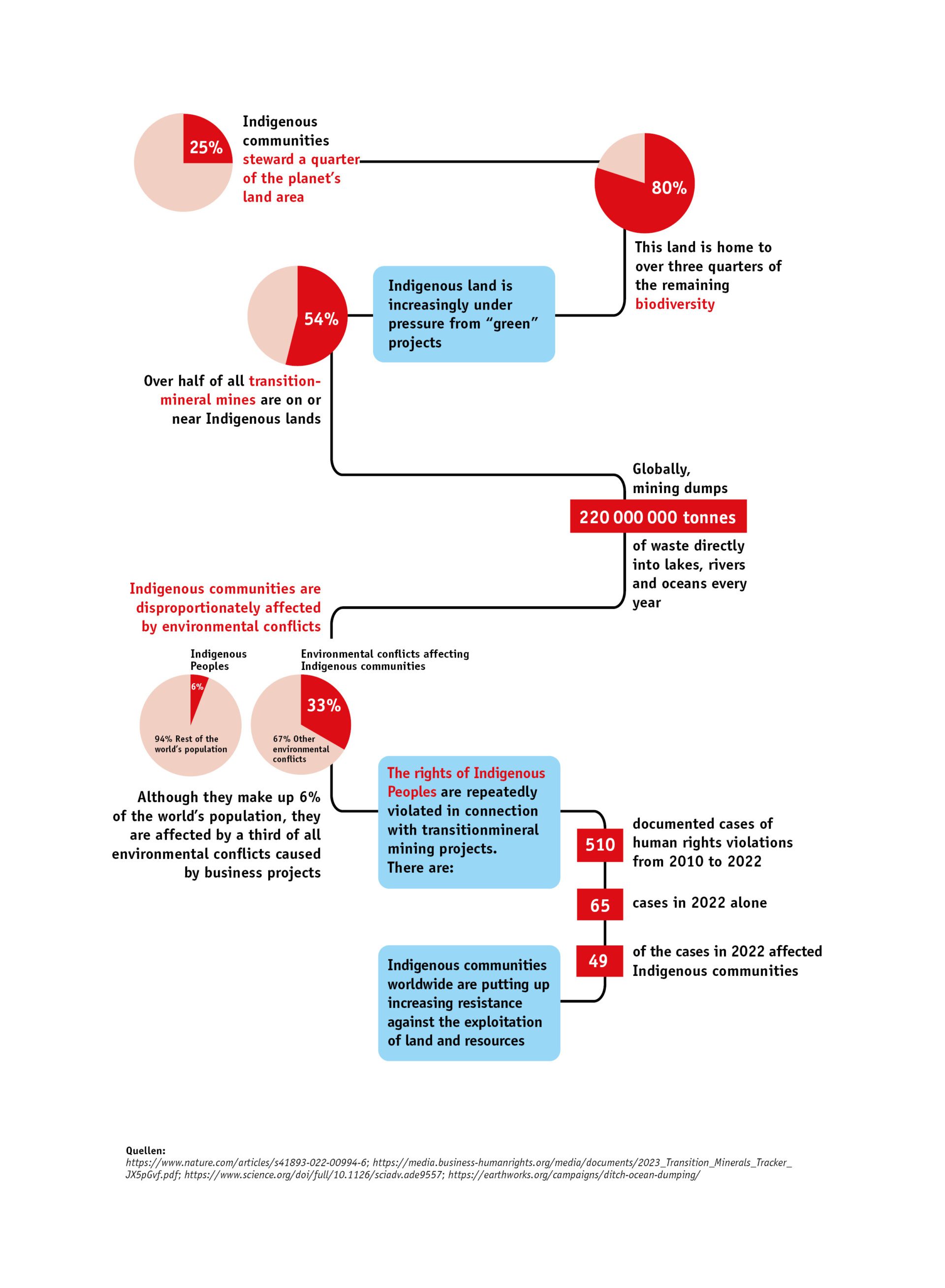

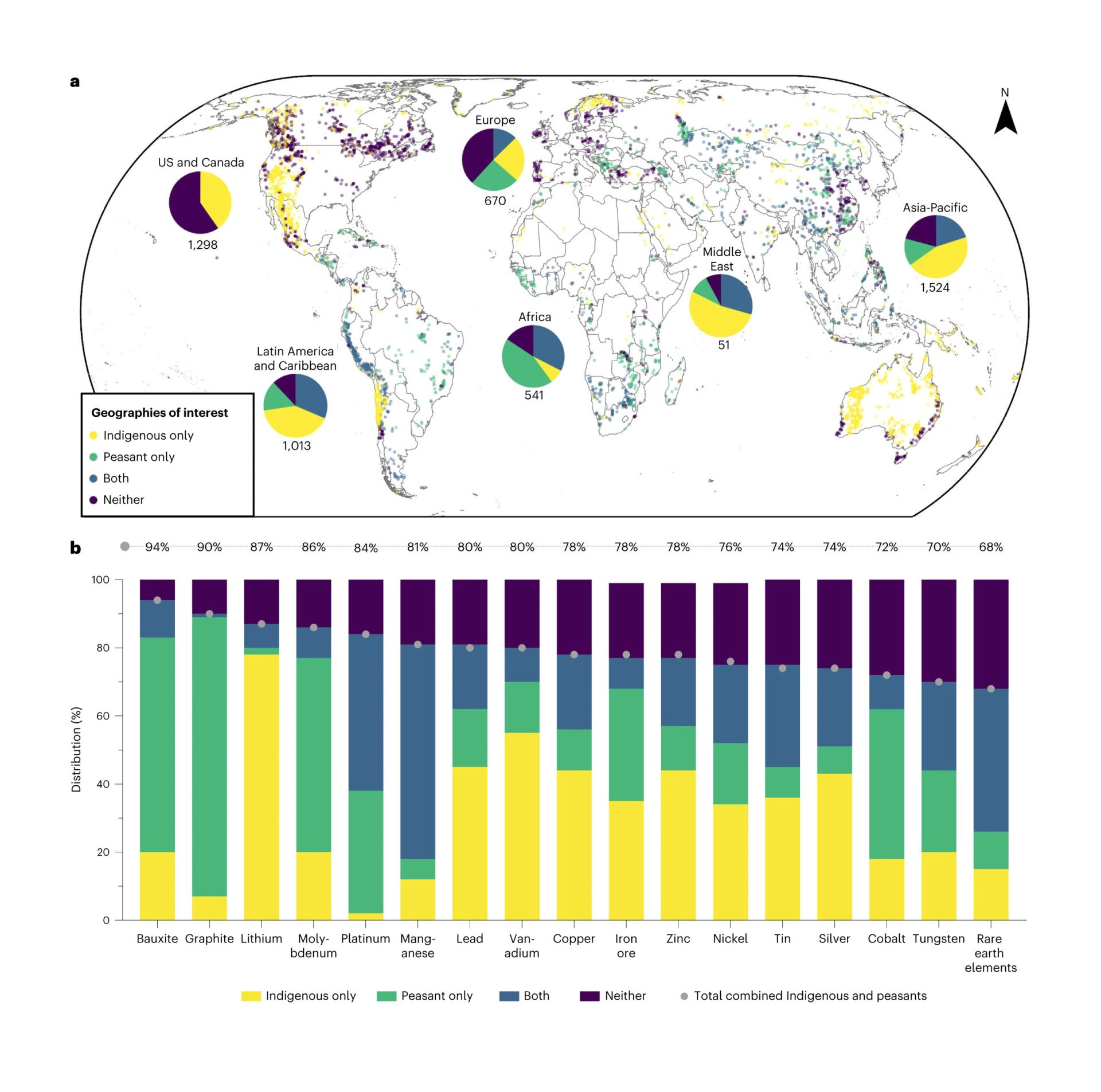

The mineral-intensive energy transition has taken raw material extraction into a new phase, and more mining projects are placing increased demands on land. The energy transition is thus creating new ecological and social risks, which also have an impact on the rights of Indigenous communities. A 2022 study, which investigated 5,097 mining projects involving a total of 30 transition minerals worldwide, showed that 54% of these projects are located on or near Indigenous lands (further information on page 6). The planning and implementation of mining projects puts pressure on the rights of Indigenous Peoples such as the right to self-determination and the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), as set out in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Mines have many negative effects on the surrounding natural environment and the communities living nearby. They present a major risk for the water systems: mines require large volumes of water, yet most of them are located in areas that are subject to water-related risks, such as water scarcity. 65% of all lithium resources, for example, are found in regions of moderate to very high water risk. Consequently, mining presents an even greater threat to the drinking and agricultural water supplies of Indigenous communities, as well as contaminating or poisoning the water that is still available. Additionally, over 220 million tonnes of mining waste is dumped directly into lakes, rivers and oceans worldwide on an annual basis, causing lasting water contamination. The negative effects of mines are not always visible at first sight. Long-term environmental pollution and destruction are often difficult to pinpoint and are a form of “slow violence”. Moreover, mineral extraction often displaces communities and involves large-scale infrastructure that extends far beyond the mine itself, such as roads, harbours and dams. This is also true of other energy transition projects, such as hydro, wind and photovoltaic schemes, which even without mineral extraction, take up land and thus severely restrict the space available for human habitation.

There is nothing new about Indigenous land being exploited without the consent of local communities. That this is now being continued under the guise of “green” solutions represents a type of “green colonialism” which is repeatedly criticised by Indigenous activists. The term “green colonialism” describes the continuation of colonial land tenure and exploitation of land under the guise of protecting the environment. The exploitation of people and nature for profit and economic growth is now being justified in the name of the “green economy”. Thus the Fosen windfarm in Norway, built on Indigenous land, exemplifies a form of “green grabbing”. This term describes the (colonial) appropriation of land and resources for ecological purposes. It is absurd to describe such projects as “green”, as they exacerbate practices associated with expropriation and exploitation and multiply injustices. This is why the STP advocates not basing climate crisis solutions on the violation of the rights of Indigenous Peoples. Consequently, the STP demands Indigenous self-determination be respected through the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) for all projects that affect Indigenous communities, and thus prioritises solutions and approaches focusing on climate justice.

The SIRGE coalition

Securing Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in the Green Economy (SIRGE) is an international coalition whose steering committee comprises Indigenous representatives from the world’s seven Indigenous regions. The aim of the SIRGE coalition is to safeguard and defend the rights of Indigenous Peoples in the “green economy”, focusing particularly on the demand for Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). The SIRGE Coalition is composed of five organisations: Cultural Survival, First Peoples Worldwide, the Batani Foundation, Earthworks and the Society for Threatened Peoples Switzerland.

Examples of SIRGE coalition activities:

- Support for Indigenous communities in their resistance against rights violations by natural resource companies, for example by means of grants, research, networking, campaigns and shareholder advocacy

- Dialogue with electric vehicle and battery manufacturers and mining companies about how they can respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and anchor these within their internal guidelines and processes

- Lobbying activities in Brussels and the United States, in order to anchor the rights of Indigenous Peoples

within all relevant legislation linked to the energy transition

The right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC)

The right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) safeguards the right of Indigenous Peoples to give, withhold or withdraw consent to any activity impacting the lands on which they live. Mining and infrastructure projects are particularly important in this context. FPIC encompasses the operational implementation of Indigenous Peoples’ right to self-determination with respect to land, territories and resources. It ensures that Indigenous Peoples are able to decide whether and in what form projects take place on theirland. The SIRGE coalition and the STP are committed to ensuring that this right is respected. The principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) is set out in the United Nations Declarations on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Definition of Free, Prior and Informed Consent

Free

Consent is given voluntarily and without coercion, intimidation or manipulation. The process is selfdirected by the community from whom consent is being sought and unencumbered by externally imposed expectations or timelines.

Prior

Consent is sought sufficiently in advance of any authorization or commencement of activities, and allows the time necessary for Indigenous Peoples to undertake their own decision-making processes.

Informed

Consent is properly solicited when Indigenous Peoples are given objective and accurate information related to the proposed activity in an accessible manner and form.

Consent

Consent is the collective decision made by Indigenous Peoples, which is reached through conventional decision-making processes. Consent may also be subject to conditions set forth by Indigenous Peoples.

Conflicts stemming from transition minerals on Indigenous land

Dissimilar geographies: the worldwide distribution of transition mineral mining projects

Indigenous communities steward over one quarter of the land on our planet, which is simultaneously home to 80% of its remaining biodiversity. They steward nearly one fifth of the total carbon sequestered by tropical and subtropical forests (218 gigatons), while 40% of the world’s protected areas are under Indigenous stewardship. The territories of Indigenous communities thus overlap with the least intensively used natural areas worldwide. Despite the responsibility for the environment shouldered by Indigenous communities, they are disproportionately affected by the climate crisis (as a result of the rising sea level, extreme weather events, droughts, forest fires and coastal erosion).

In addition, Indigenous communities are particularly negatively affected by the proposed solutions to enable the energy transition and their consequences, specifically the increased extraction of transition minerals on their territories (see diagram). Thus a 2022 study examined 5,097 mining projects involving 30 transition minerals. The mines are indicated by points on the map above. The study comes to the conclusion that 54% of the projects are located on or near Indigenous Peoples’ lands. Indigenous territories are now disproportionately affected not only by the climate crisis but equally by the proposed solutions; this implies the maintenance of colonial landowning relationships and exploitation. The expropriation of Indigenous territories for raw material mining and industrial development is leading to environmental conflicts.

Geopolitical context

The energy transition has resulted in a rapid and massive increase in the demand for transition minerals. According to the political context, transition minerals are also described as “critical minerals”. The term encompasses a range of minerals such as lithium, copper, cobalt, nickel and rare earths, which are seen as indispensable for the energy transition and the associated technologies, and which may be subject to supply chain interruptions. This is leading to geopolitical tensions: governments worldwide are attempting to safeguard their access to natural resources by means of “strategic” mines and partnerships. In many cases this is leading to accelerated approval processes, such as authorisation of new mining projects; this acceleration is also referred to as “fast tracking”. An example of this is the lithium mine at the Thacker Pass (Peehee Mu’huh), characterised by the US government as “strategic” and therefore authorised by fast tracking. A consequence of this was that Indigenous communities for whom Peehee Mu’huh is an important location were not appropriately consulted, neither by the US government nor by the mining company.

Fast tracking procedures are supported by new regulations. In the EU, for instance, the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) is currently being finalised. The legislative package aims to stimulate regional extraction of “critical” raw materials and to safeguard and diversify imports from non-EU countries. The aim is thus to

guarantee supply chains not just for the “green” and digital transformation but also for military technologies.

Countries such as Australia, Brazil, Peru and South Africa have also altered the statutory bases for mining projects. The aim is to incentivise increased mining investment by means of looser regulation.

The economic transformation and the growing demand for transition minerals have led to a boom in investments associated with them, which Swiss companies and banks also find increasingly attractive. As investments of this kind are seen as urgent, environmental issues are now being played off against the rights of Indigenous Peoples, and new conflicts have arisen.

“Green” projects on Indigenous lands

Case studies of transition minerals mining in Indigenous areas

Indigenous communities are disproportionately impacted by the negative effects of mining, as demonstrated by the Global Atlas for Environmental Justice (EJAtlas). This documents worldwide cases of environmental injustice, totalling 1,044 conflicts affecting 740 Indigenous communities. Mining is responsible for almost a quarter of these environmental conflicts and is thus the leading cause of them in the economic sector. Indigenous communities throughout the world are increasingly protesting and taking legal action to stop the recurrence and exacerbation of colonial exploitation and violence in the mining of transitional minerals.

USA: lithium at the Thacker Pass/Peehee Mu’huh

The Lithium Americas company started lithium mining on the Peehee Mu’huh mountain in March 2023. Peehee Mu’huh has great historical, cultural and religious significance for the Indigenous communities living there. This dates back to the massacre of the Indigenous Paiute tribe by the US cavalry in 1865. Since then, Peehee Mu’huh has been a sacred burial site for the Paiute. There is significant opposition to mining on Peehee Mu’huh, as Indigenous activists and groups are energetically protecting the land. Apart from the cultural significance of the place, they also expect the mine to destroy important habitat for wild animals and contaminate the groundwater. With slogans such as “Life over lithium”, they are fighting against the mine and making it clear that the profits of the Lithium Americas company must not be set above the preservation of the world they live in.

Indigenous communities raise awareness about the impact of the proposed lithium mine at Peehee Mu'huh on their sacred burial site, water resources, and wildlife. Photo: Chanda Callao/@Peopleofredmountain

In January 2021, the US government issued the mining licence, valued at $2 billion. The US government fast-tracked the legal process for starting lithium mining, as a result of which the right of the Indigenous communities to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) was ignored. It gave Canadian-based Lithium Americas the building lease. According to the Lithium Nevada Corporation, a subsidiary of Lithium Americas, the Thacker Pass mine will be North America’s largest source of lithium.

Peehee Mu’huh exemplifies the increase in the number of lithium mines. In the United States, a disproportionately large number of transition mineral mines are within 35 miles of Indigenous lands: this applies to 97% of nickel mines, 89% of copper mines, 79% of lithium mines and 68% of cobalt mines. The “People of Red Mountain” Indigenous group is fighting for its land, and has lodged an appeal against the mine at Peehee Mu’huh. The legal battle is not yet over. Meanwhile, the Lithium Nevada Corporation filed a suit against the activists’ Camp Ox Sam, set up to halt the mine. The camp was cleared on 8 June 2023. The

SIRGE coalition is supporting the “People of Red Mountain” in their struggle to have their right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) respected.

Russia: Nornickel nickel and lithium mine

Commodity group MMC Norilsk Nickel, known as Nornickel, mines nickel on the Russian island of Taimyr. Nickel, like lithium, is required in the mobility revolution for, among other things, the batteries of electric vehicles. The mining causes severe air pollution. In addition to generating air pollution, the company also disposes of toxic residues in the natural environment around the large town of Norilsk. It is also responsible for one of the worst environmental catastrophes in the Arctic, which occurred in May 2020. As a result of negligence, 21,000 tons of diesel oil was released into the natural environment around the Siberian town – which is also Indigenous land – severely polluting two rivers. The catastrophe had a huge impact on the Indigenous communities: the reindeer left the area because of the contamination, and the toxins killed not only the fish but also th insects that were their food. This led to reduced sales of meat and fish, and thus to an income shortfall that led to the affected communities being able buy less food of other kinds.

The polluted Piassino River after the Nornickel diesel oil spill in 2020. Photo: provided

Nornickel also has a Swiss subsidiary, Metal Trade Overseas SA, based in Zug. From Switzerland, the company markets throughout the world the raw materials it produces in Russia and Finland. Nornickel is only paying lip service to the problems created for the Indigenous communities – such as the contamination of the environment and the threat to their way of life – and shows no interest in face-to-face dialogue with representatives of the communities. While the company did indeed take action, no dialogue on an equal footing was held on the implementation of the process with Indigenous representatives; and the little compensation that was given went only to those who were uncritical of the company. The STP has supported the Indigenous partners in their demand that Nornickel respect the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC).

Plans have recently been unveiled for a lithium mine on the Kola Peninsula in the Murmansk region, as part of which Nornickel has signed a cooperation agreement with Russian state atomic energy company Rosatom. The mine will be in Europe’s largest wilderness area, which has until now been completely free of infrastructure such as roads. The region of the planned mine is stewarded by the Indigenous Sámi, Nenzenand Komi Peoples. These communities fear severe contamination of the area and dramatic consequences for their way of life, and are sceptical of Nornickel’s readiness to undertake consultations. While Nornickel and Rosatom hope to obtain a mining licence by as early as late 2023, according to Andrei Danilov, an STP partner, only a small number of the affected communities have been contacted at all, and only then at the last minute.

Norway: Nussir ASA copper mine at Repparfjord

In 2014, mining company Nussir ASA planned to build a copper mine on Sámi land near the Repparfjord in Norway. Nussir ASA planned to extract 50,000 tons of copper ore from the localities of Nussir and Ulveryggen (EJA). The copper ore extraction and the building of the infrastructure required for this was to take place on Sámi reindeer grazing land and would have severely restricted reindeer grazing. Moreover, it has been planned to release mine waste via an underwater disposal system directly into the fjord. Swiss bank Credit Suisse (CS), as nominee shareholder for then unknown clients, was also involved, with a 20.6% shareholding in Nussir ASA. In 2019, the STP launched a campaign against the involvement of CS, with the slogan “Stop banking against the Sámi!”, in order to put public pressure via the media on the Swiss bank and raise awareness of its responsibility as regards the violation of the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Nussir ASA has been planning a mine in the Repparfjord in Norway for several years. Photo: Lea Ackermann / GfbV

The copper mine would have threatened the environment and, because of a lack of consultation processes, would have violated the rights of the Sámi communities and negatively impacted their livelihoods. In March 2019, the Naturvernforbundet environmental organisation, the Sámi Parliament and reindeer herders together filed a lawsuit against the granting of an operating licence to Nussir ASA. They did so on the grounds that granting the licence violated the national and international rights of the Indigenous Sámi people. In December 2020, CS responded to the demands of the Sámi communities and the STP: The bank ceded the administration of the shares of Nussir ASA and revealed the identity of the previously undisclosed share owner, who contacted the Sámi after the talks.

This did not put an end to plans for the copper ore mine. However, in summer 2021, young activists joined local fishers and Indigenous Sámi people on the shores of the Repparfjord to block construction of the mine by Nussir. Their presence caught the attention of Aurubis AG, Europe’s biggest copper producer, which announced that it was terminating its purchasing agreement with Nussir owing to sustainability concerns. Currently construction of the mine is on hold after various investors also pulled out. Nonetheless, there are

still plans to build a mine, so the story is not over yet.

Norway: Fosen wind farm in Storheia

On the Fosen peninsula in Norway, the Fosen Vind DA company’s wind farm is making large parts of the reindeer winter pasture unusable, resulting in Sámi reindeer herders losing the greater part of their livelihood. The Fosen Vind DA consortium includes two Swiss companies as joint investors: Energy Infrastructure Partners (EIP), with headquarters in Zurich and BKW Energie AG, based in Bern. In 2013, reindeer herders lodged an appeal against the siting of the wind farm on Indigenous land with the Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. The ministry rejected the appeal, as a result of which the case went to Norway’s Supreme Court. In a sensational judgement in 2021, the court ruled in favour of the Sámi. It declared that the 151 wind turbines built on Indigenous land in Storheia were illegal. Together with the representatives of the South Sámi, the STP demanded, in their “Turbines Need Sami Consent” campaign, that investors Statkraft and Nordic Wind Power DA (of which Swiss energy producers EIP and BKW are part) stop the project, withdraw their investments and guarantee the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) for Indigenous communities.

In March 2023, Sámi and climate activists call on the Norwegian government in Oslo to enforce the rights of Indigenous Peoples. Photo: Shutterstock

Although the Norwegian Supreme Court judged in favour of the Sámi, Europe’s biggest wind farm continues to operate. Five hundred days after the judgement, Sámi protesters and climate activists occupied the square in front of the office of Norwegian prime minister Jonas Gahr Støre. The activists – including Greta Thunberg, who attended the protest – insisted that the transition to “greener” energy should not take place at the expense of the rights of Indigenous Peoples. One of their slogans was “Respect existence or expect resistance”. The Norwegian government has since apologised and promised to accelerate the search for solutions that will implement the judgement; the reindeer herders are to take an active part in this process.

Solutions for climate justice rather than “greenwashing”

The cases described above are representative: new mines and “green” projects are causing additional environmental conflicts, but Indigenous resistance is also increasing. Indigenous communities worldwide have campaigned for their right to self-determination and to prevent their lands being sacrificed in the name of instant solutions to the climate crisis. The pretext of urgency must not be used to create an antagonism between the energy transition on the one hand, and self-determined stewardship of land and the environment by Indigenous communities on the other. In the case of the Thacker Pass, the mine also threatens biodiversity, while the Fosen wind park jeopardises Indigenous reindeer herding. Governments and companies accept this as a necessary evil.

This is also shown by projected new regulations such as the EU law on “critical” raw materials mentioned earlier. The accelerated processes are justified with the argument of the need for instant solutions and are another obstacle for the self-determination of Indigenous communities. They give rise to “greenwashing”, a process by which companies and governments market profit-led projects as being ecological and climate friendly, in order to distract attention from negative consequences for human beings and the environment.

Solutions embodying climate justice are needed, so that no new injustices are created and the interests and rights of Indigenous communities are respected. Climate justice stands for a more comprehensive understanding of possible ways out of the climate crisis and views social and ecological justice as an indivisible whole. The term is derived from “environmental justice”, as coined by non-white and Black activists in the United States during their struggle against the disposal of contaminated waste in non-white neighbourhoods. Part of climate justice is the demand for a just transition. It also includes the recognition that there is an unjust division between those who cause the climate crisis and those who suffer its effects. This is particularly evident in cases of Indigenous self-determination involving land and resources. In the end, climate justice, energy transition and the rights of Indigenous Peoples must all be part of a whole.

A comprehensive rethinking of the energy transition is required, one that puts the well-being of the communities and ecosystems most affected by the climate crisis front and centre. Possible solutions for mobility include reducing the number of private car journeys and maximising the circular economy, i.e. through battery recycling and reducing battery size. The SIRGE coalition, and thus the STP, demand the guarantee of the participation of Indigenous communities in whatever situation has, or could have, consequences for them and their land, being guided by Indigenous values and solutions. The key principle for concluding agreements and partnerships is that projects should be carried through from beginning to completion using the protocols formulated by the Indigenous communities, incorporating the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC).

Demands of STP

The Society for Threatened Peoples is committed to the rights of Indigenous communities in the energy transition – particularly as regards the mining of transition minerals for electro-mobility. It advocates for Indigenous communities that are affected by mining and infrastructure projects for the manufacture of renewable energies (such as wind or solar installations) being consulted in advance and enjoying self determination in terms of giving or withholding their free and informed consent. The failure of a state to implement international standards in respect of the rights of Indigenous Peoples does not lessen the expectation that companies should adhere to those standards.

The Society for Threatened Peoples demands that governments:

- Strictly adhere to and implement the rights set out in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), in particular the right to territorial self-determination - Create overall institutional conditions guaranteeing the maintenance of the rights of Indigenous Peoples in raw material mining

- For mining projects that affect the way of life and territories of Indigenous communities, obtain their Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) at every individual stage of a mining project, from exploration to completion and land restoration. In doing so, self-determined decision-making that is led by Indigenous

Peoples should be guaranteed. - Sign and ratify the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (ILO Convention 169), where this has not yet been done

The Society for Threatened Peoples demands that Swiss politicians and authorities:

- Adopt a strong corporate responsibility law, as provided for in the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). This should make companies liable for breaches of due diligence. It should also provide for independent oversight that can investigate complaints and sanction companies. It should make companies liable in the event of a breach of due diligence.

- Guarantee disclosure of business relationships

- Enshrine, along with environmental standards, minimum standards in respect of human rights and the

rights of Indigenous Peoples in trade and investment protection agreements - Enshrine responsible use of transition minerals in the 2030 Sustainable Development Strategy, in the

associated action plan and in the “Business and Human Rights” national action plan. - Reduce use of raw materials: establish demand reduction goals (for production and consumption), promote the circular economy (e.g. recycling of batteries for electric vehicles), set efficiency standards, and create incentives for the purchase of smaller vehicles with lighter batteries

- Ratify the “Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention” (ILO Convention 169)

- Prevent greenwashing in the entire economic chain and especially in the financial market by anchoring

human rights due diligence as a minimum standard for financial products marketed as “sustainable”

The Society for Threatened Peoples demands that the business sector and companies:

Respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and in particular the right of Indigenous communities to Free,

Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), which for the STP means:

- In the planning, construction, operation and completion of projects:

- Enshrining the rights of Indigenous Peoples, including FPIC and UNDRIP in internal guidelines and guaranteeing an FPIC process with Indigenous communities

- Certifying projects by initiatives with strict human rights and environmental standards, which are audited by independent third parties and jointly managed by civil society (e.g. IRMA in the case of mining)

- When investing in and financing projects and procuring raw materials:

- Enshrining the rights of Indigenous Peoples, including FPIC and UNDRIP, in internal guidelines, in the

code of conduct for suppliers and in risk management processes, and to monitor their implementation - Acquiring membership of initiatives with strict human rights and environmental standards, which are monitored by independent third parties and jointly managed by civil society (e.g. Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance - IRMA)

- Enshrining the rights of Indigenous Peoples, including FPIC and UNDRIP, in internal guidelines, in the

Important: companies cannot outsource their own responsibility for human rights to voluntary standards of

this kind, but should only use these as one instrument among others.

The Society for Threatened Peoples appeals to the public to:

- Make their own contribution by giving up throwaway consumption habits in favour of circular economy

behaviour (such as by recycling, repairing, reusing and repurposing products) and using public transport

rather than personal vehicles, in order to minimise the problematic extraction of new raw materials. Prioritise small vehicles with small batteries when buying a new car - As investors, invest only in companies that have committed to high human rights and sustainability

standards

The Society for Threatened Peoples appeals to all those involved in environmental and climate protection

to:

- Demand climate justice solutions for the energy transition that see the rights of Indigenous Peoples and

the interests of communities affected by raw material mining as being of equal value to climate goals and inseparable from them - Call for the right to self-determination for Indigenous communities and their right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) in the energy transition

The energy transition, urgent and necessary though it is to protect the climate, must not bring about new human rights abuses. Solutions are needed for climate justice that respect Indigenous and human rights.

More on the program “Climate Justice! Respect Indigenous Consent”:

Publication details

Publisher: Society for Threatened Peoples (STP)

Text: Nadira Soraya Haribe

Layout: Tania Brügger Márquez

Address: Birkenweg 61, CH-3013 Bern / Tel.: +41 (0) 31 939 00 00

Donations: Berner Kantonalbank BEKB: IBAN CH05 0079 0016 2531 7232 1

Edition: September 2023