UBS has stated that it wants to be one of the largest investment banks in South America. To this end, it is supporting agricultural corporations in Brazil – including problematic ones. For instance, this major Swiss bank has provided the two agricultural corporations BrasilAgro and Marfrig with money from global investors. The two corporations are involved in severe cases regarding illegal deforestation, environmental destruction and the violation of indigenous rights. This is shown by research carried out for the STP by the Center for Climate Crime Analysis (CCCA).

Year after year, huge areas of the Amazon rainforest are destroyed in Brazil. During the first half of 2022 alone, a record expanse was deforested, almost exactly equivalent to the Swiss Alps’ entire forested area. One key driver of this destruction is Brazilian agriculture, which is profiting from international land speculation and the rising demand for products such as soya and beef.

Illegal clearing often occurs in order to obtain land for crop and livestock farming. Such land-grabbing is a lucrative business for agricultural corporations (see box). The consequences are borne by indigenous as well as traditional communities: Animals that are hunted by the communities flee or no longer find sufficient habitat. Due to the use of pesticides, fish die and plantings of indigenous communities are destroyed. Last but not least, more and more indigenous leaders come under pressure: Those who stand up against the industry are often massively threatened or even killed.

The indigenous woman Marcele Mundurukú already described the threat of land-grabbing in her area in an interview with the STP last year:

“At first, you think the plantations are still far away, but year after year, more land is cleared and suddenly [the invaders] are in indigenous territory, felling trees, setting fires and threatening us. We have already made numerous complaints, but the authorities won’t show up.”

Marcele is a resident of the lower Tapajós Basin in the Amazon rainforest. While this area is not directly subject of this report, her narrative provides a powerful illustration of the threat posed by land-grabbing.

Marcele Mundurukú, about deforestation in the Lower Tapajós area, Pará. Photo: Thomaz Pedro

‘Grilagem’ – land-grabbing via (slash-and-burn) clearing in Brazil

Land-grabbing is the large-scale (legal or illegal) appropriation of land by financially powerful players, such as major landowners, banks or investors. Land-grabbing can be carried out by private individuals or even state institutions.

In Brazil, land-grabbing is particularly widespread in states where agriculture plays an important role. The demand for soya and beef is so high that more and more untouched land is being converted for industrial use. The first step in this process is to fell trees so they can be sold. After that, the remaining vegetation is removed and burnt down, then the area is staked out. In order for the newly obtained land to be declared ‘productive’, seeds are sown for agricultural products or cattle pasture grass. This enables the site to be officially recognised by the authorities as an agricultural area.

The problem is widespread in Brazil, including in areas of the Mundurukú indigenous people of the lower Tapajós. Like Marcele (see above) Paolo Mundurukú, who lives at the lower Tapajós, says:

“We’ve seen tractors with a chain hooked to one tractor at one end and to another tractor at the other end, clearing the forest with it – I don’t know how many hectares of forest per day. They cut down the forest and set fires to destroy all the vegetation, the hardwood, everything. They burn everything. They then blame the locals, saying that we’re destroying the forest, whereas they’re the ones doing it.”

Paulo Mundurukú, farmer in the Lower Tapajós area, Pará. Photo: Thomaz Pedro

There is a long-standing tradition of acquiring agricultural land by means of illegal land-grabbing in Brazil, where it has a distinct name: ‘grilagem’. The term is derived from the Portuguese word for crickets: grilos. This is because the land-grabbers (‘grileiros’) apparently used to put forged documents in a box full of crickets, which would then chew up the paper. This would quickly make the documents look old, so they could serve as proof that the recently cleared forest had already been in use as agricultural land for a long time. Today, most of the relevant documents are forged digitally.

‘Grilagem’ is best documented in the Amazon region: According to the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), over a third of the deforestation that occurred in the Amazon region between August 2018 and July 2019 can be traced back to ‘grilagem’. Brazilian law stipulates that the owners of such properties are responsible for the damage to the environment and must repair it, regardless of whether or not they caused the deforestation themselves.

A lot of money is at stake: Brazil's exports consist of 50% agricultural products. Brazil is the world’s second-largest beef producer after the USA – and with 34 percent of the world’s soya production, it is the largest soya producer, ahead of the USA, with China being the largest importer of the bean.

Since 2020, it has been clear that the major Swiss bank UBS also wants to make money from the Brazilian agricultural sector: Together with state-owned Banco do Brasil, it founded the investment bank UBS BB, which provides the Brazilian agricultural sector with money from global investors. As a new player, half a year after it was founded, this investment bank helped raise money for Marfrig and BrasilAgro, two highly controversial corporations in Brazil. In 2021, UBS BB organized the issue of so-called "Agribusiness Receivables Certificates" (CRA) using this financial instrument to help the Brazilian agricultural sector gain international investors. BrasilAgro and Marfrig thus received capital to finance their at times controversial business.

According to Sylvia Coutinho, president of UBS in Brazil, the bank wants to contribute to the transformation of Brazilian agriculture into a greener industry. She said, the sector understood that without the environmental issue and a "green label," growth in the industry was limited. The priority, therefore, was to increase productivity, not to open up new areas. Asset management for corporate families in the agricultural sector is UBS BB's second pillar.

Marfrig and BrasilAgro: Profits at the expense of the environment and human rights

Beef giant Marfrig is one of the world’s largest producers of hamburger meat and Brazil’s third-largest food company. In Brazil alone, 11’100 are slaughtered every day across Marfrig’s twelve company sites, after being raised by suppliers. On behalf of the STP, the Center for Climate Crime Analysis (CCCA) has analysed suppliers for two slaughterhouses: One in the municipality of Tangara da Serra (Mato Grosso state) and one in the municipality of Tucumã (Para state; although according to Marfrig, the operation in Tucumã was suspended in 2020).

This research shows that from 2018 to 2020, these two Marfrig entities purchased some of their cattle from indirect and direct suppliers based in indigenous territories and nature reserves. The Onça Parda farm, an indirect supplier of Marfrig in the state of Mato Grosso, furthermore operated in the indigenous territory of the Manoki. Two other indirect suppliers (Pinhão Roxo and Estrela) were located on the indigenous territory of Cachoeira Seca, in the state of Para. When confronted with these facts, Marfrig replied that these farms were no longer part of their supply chain. According to the company, Onça Parda is no longer a supplier since 2019, and the Pinhão Roxo and Estrela farms were closed in 2020. suppliers’ land from 2009 to 2020. This amounts to an area seven times the size of the Swiss National Park.

The company BrasilAgro is one of the companies in Brazil with the largest area of arable land. The company’s core business is the acquisition of ‘unproductive’ real estate and conversion thereof into agricultural land. The properties thus obtained are either sold for profit or used for the cultivation of soya in particular. Research conducted by CCCA for the STP shows that this business model is based on repeated unauthorised deforestation: For instance, between 2009 and 2020, a total area of 300.73 km² was deforested on BrasilAgro’s properties without authorisation. This amounts to an area almost four times the size of Lake Zurich.

Deforestation hotspots

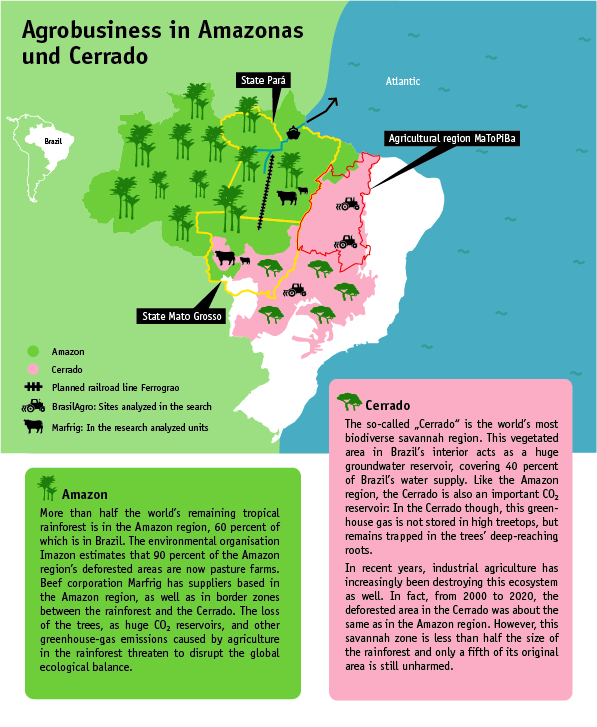

The corporations BrasilAgro and Marfrig operate in regions that have become wealthy as a result of the environmentally damaging boom in agriculture. BrasilAgro is thus active in MATOPIBA, a region in the north-east of Brazil that extends across the states MAranhão, TOcantins, PIauí and BAhía. Matopiba was first established at the beginning of the century to promote agriculture in the area. The name comes from the respective states through which the boundary around the Cerrado savannah area runs. The region offers ideal conditions for large-scale agriculture, due to the Cerrado’s huge water reserves and flat landscapes. As a result, its agricultural industry is undergoing massive growth, primarily in soya monoculture, a consequence of the demand for fodder that is used in global meat and dairy production. In this region, according to the Brazilian network MapBiomas, almost three quarters of the Cerrado has already been destroyed.

Beyond the demand for agricultural products, the expansion of the agricultural industry in Brazil is also driven by international investors. A report by FIAN International shows that, since the 2008 financial crisis, the agricultural land business has become more profitable than agricultural production itself. The former now has little to do with fodder production and is entirely focused on trading and managing agricultural property. Land-grabbing and falsification of documents are directly linked to this development, as acquisition of land is a central component of land speculation.

Besides Matopiba, land-grabbing is also big business in the states of Pará and Mato Grosso. Marfrig has suppliers in both, BrasilAgro properties in the latter. These two states have had the worst forest-fire statistics in the Amazon region since such statistics began in 1988. While Pará has spent 16 years as the record holder for forest fires, Mato Grosso has the highest number of cattle nationwide.

UBS opens doors for agricultural investment in Brazil

The Amazon region and its inhabitants are in acute danger, especially in Brazil. Right-wing populist President, Jair Bolsonaro, wants to ruthlessly exploit the Amazon and other unique ecosystems such as the Cerrado, allowing large-scale mining, logging and agriculture in nature reserves and indigenous areas. His policy of introducing anti-indigenous laws, cutting environmental authorities’ funding and publicly speaking out against indigenous rights is underpinned by the interests of the agricultural lobby. Under these circumstances, financial backers run a high risk of getting involved in problematic business activities. By providing financial services for firms like Marfrig and BrasilAgro, UBS BB is supporting a sector that is contributing to the exploitation of the environment and the violation of indigenous rights. The risks arising from UBS's operations in the Brazilian agricultural sector were highlighted in an article by Olivier Christe and Fernanda Wenzel in the online newspaper "Republik" back in spring of 2021 (article written in German): In addition to its proximity to the Bolsonaro government, the article highlighted weaknesses in supply chain transparency for livestock and soy in Brazil's agricultural sector.

“Directly or indirectly, the Europeans are contributing to the devastation of the Amazon region, be it via financing from banks, or in trade. In any case, they are complicit in what is happening in Brazil’s indigenous territories. When Europe provides funding, it contributes to the death of indigenous peoples and the death of our lands.”

Auricelia Arapiuns, Co-director of the indigenous organisation CITUPI. Photo: Thomaz Pedro

In order to comply with the OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises on human rights and environmental protection, UBS must ensure that it is not helping either BrasilAgro or Marfrig to engage in problematic activities. The STP asked the bank what measures it was taking to reduce the risk of its CRA activities having a negative impact on the environment and human rights. UBS replied: "Due to bank client confidentiality, we cannot provide any information about (potential) clients or client relationships" (translated by STP).

Self-regulation does not work

UBS has its own specific guidelines regarding risks related to sustainability and the climate. According to the bank, these also cover the business activities of the investment bank UBS BB. In these guidelines, deforestation is explicitly mentioned as a risk:

“It is estimated that more than half of deforestation worldwide can be attributed to the conversion of forest into cropland, while livestock farming is responsible for almost 40% of the lost forest area.” (p. 4)

However, these same guidelines and the standards within them have enormous loopholes, making business with firms like BrasilAgro and Marfrig possible. Two things in particular are controversial:

- The livestock-farming risk sector: Although UBS initially acknowledges that livestock farming is responsible for almost 40 percent of the world’s lost forest area, there are - in contrast to the risk sectors of palm oil, soy and wood - no publicly accessible criteria for this sector that any UBS business activity has to meet. In response to an STP inquiry about this gap, UBS responded: "The rationale for our additional standards on palm oil, soy and timber is the availability of a robust certification process covering these commodities, and providing third-party assurance of a company’s performance. A similar certification process currently does not exist, to the best of our knowledge, for livestock." (Email from UBS dated August 16th, 2022).

- The soya risk sector: Just a few days before entering into its deal with BrasilAgro, UBS adjusted its criteria for business dealings with soya companies. In the STP’s view, this adjustment lowers the standard considerably. Before the change, soy companies like BrasilAgro had to be a member of the “Roundtable on Responsible Soy (RTRS)” standard. Now it can be sufficient if the company draws up a plan to commit to a similar standard by a certain date in the future. In the STP's view, this carries the risk that this plan will never be implemented. From UBS's point of view, its standard remains equivalent: “We disagree with your assessment that UBS’s soy standard has deteriorated.” According to the bank, its approach remains strict. However the weakening is also reflected in the evaluation by the ranking platform Forest500: instead of 2/3 of the possible score in 2020, UBS achieves only about 1/3 of the score for its soy policy in 2021.

The STP is of the opinion that it was irresponsible of UBS BB to help the company BrasilAgro obtain capital, despite its main activity being the conversion of ”unproductive” land into industrial agricultural areas as well as having been associated with unauthorized deforestation several times in the past.

Back in 2013, the Brazilian environmental agency IBAMA, fined BrasilAgro $2.5 million dollars for illegal logging of protected areas. In 2017, it was again publicly disclosed that BrasilAgro had cleared more than 21,000 hectares of native forest on its lands. In 2021, at the time of the deal between UBS BB and BrasilAgro, the judgment on deforestation was still pending.

Moreover, the STP’s research and satellite images show repeated unauthorised deforestation on almost a third of BrasilAgro’s properties from 2009 to 2020.

With regard to Marfrig, the STP also criticises the fact that UBS BB has provided financial resources for a company with such a poor record in terms of environmental and social responsibility. Marfrig itself acknowledges the fact that meat suppliers are invading indigenous territories and nature reserves, and illegally clearing rainforest. The firm has been conveying an intention to tackle the problem for over ten years and has signed a corresponding agreement for the state of Mato Grosso, but not for Pará. In response to STP’s inquiry, Marfrig commented: “Even though it does not operate in the state of Pará, Marfrig is aware, however, that obtaining reliable information from indirect suppliers is still a major challenge.“ (E-Mail by Marfrig to STP, September 12, 2022)

At the time, when UBS BB entered into the business relationship with Marfrig, there were already numerous indications that Marfrig had failed to prevent links to illegal logging in its supply chains. In 2020 – almost a year before the deal with UBS BB - Marfrig published its Plano Marfrig Verde+, making it clear that they were taking another ten years’ time to work towards supply chains free of deforestation and human rights abuses. In July 2020, Greenpeace criticized this statement of intent. Nevertheless, UBS BB entered into the deal with Marfrig. In January 2022, the Norwegian Pension Fund put Marfrig under surveillance due to the risk of serious environmental damage.

Business practices in the Amazon region have massive consequences for the environment, for the indigenous population as well as for traditional communities: They lose their habitat, their income and their culture, and are exposed to violence, threats and attempts at intimidation.

A corporate responsibility law is needed

The joint venture between UBS and Banco do Brasil once again demonstrates that internal corporate guidelines are not enough. What is needed in Switzerland, is a practical law on corporate responsibility, guaranteeing that firms like UBS will have to take responsibility for any human rights violations or environmental destruction that they cause, contribute to or profit from.

The video summarizes the report "Deforestation in Brazil: UBS finances agribusinesses Marfrig and BrasilAgro exposed to environmental damage in Amazon and Cerrado" in an easy-to-understand way and shows why a corporate responsibility law is needed. If you click the YouTube icon at the bottom right and watch the video directly on YouTube, you can enable English subtitles.

Imprint

This text was prepared on the basis of research conducted by the Center for Climate Crime Analysis (CCCA) on behalf of the STP and inspired by two media articles in Republik and Mongabay by Olivier Christe and Fernanda Wenzel.

- Using satellite images, the data compiled by CCCA identifies deforestation on BrasilAgro farms and on land belonging to Marfrig suppliers. CCCA carried out the research with the kind support of HEKS. You will find it here.

- The article ‘Brandherd mit Dividende’ (German, 19/04/2021) is available here: https://www.republik.ch/2021/04/19/brandherd-mit-dividende

- The article ‘Debt deal with deforester BrasilAgro puts UBS’s green commitment in question’ (English, 06/08/2021) can be accessed here: https://news.mongabay.com/2021/08/debt-deal-with-deforester-brasilagro-puts-ubss-green-commitment-in-question/

The quotes from indigenous peoples on deforestation come from a STP research from 2020 on the situation of communities in the Amazon rainforest in the lower Tapajós Basin. This area is not the subject of this report, but the accounts of the indigenous people show the threat posed by land grabbing in general.

Bibliography for the information graphics "Agrobusiness in Amazon and Cerrado":

https://www.gov.br/mma/pt-br/assuntos/ecossistemas-1/biomas/amazonia

https://icv.org.br/2021/05/desmatamento-na-amazonia-e-cerrado-em-mato-grosso-foi-89-illegal-em-2020

https://insights.trase.earth/yearbook/highlights/expansion-and-deforestation/

The Brazilian Cerrado: the upside-down forest on the frontlines of agriculture